An initial rush of favorable polling or publicity in the next few days, if it comes, won't mean much for the Republican nominee, according to strategists in both parties and veterans of previous campaigns. Plenty of vice presidential selections enjoyed a similar rise - before plummeting into disaster.

Nor should Romney bank heavily on Ryan’s skills as a “wonk, ” or his ability to speak fluently about the budget, both traits that Romney and his aides touted as important assets in the selection of the ۴۲ - year - old Wisconsin Republican. There is virtually no chance that deeply entrenched views about entitlement programs — majority opinions that at least on the surface are strongly at odds with Ryan’s record — can be reversed in the ۱۲ weeks before Election Day.

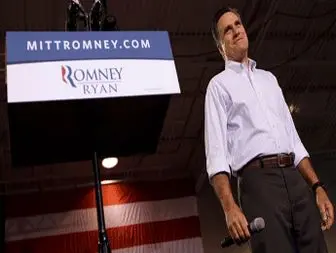

Instead, whether the Ryan selection will turn out to be shrewd or self - destructive will be mostly settled over the next three weeks, in the run - up to the party conventions and in the major addresses there. It is in this critical window, many observers believe, that Romney must make the Ryan selection less about specific policy arguments and more of a general statement about his own values — about his own seriousness, self - confidence and willingness to embrace political risk to solve big problems.

This marks a dramatic shift in Romney’s approach to winning the presidency.

(Also on POLITICO: Paul Ryan, Mitt Romney’s high - road warrior)

One way to think about the new race is in scientific terms. Romney has abandoned a strategy that relied on political mechanics in favor of one that relies on political chemistry.

A mechanical campaign aims to motivate certain identifiable blocs of voters through specific and well - rehearsed techniques — targeted appeals to well - defined demographic or geographic groups, designed to work in a classic action - reaction style.

Politics as chemistry is different. It seeks to change the relationship between the candidate and the electorate in a more fundamental way — encouraging voters to look at him and his capacity for leadership in a entirely new light, just as adding a new ingredient to a chemical solution can create an entirely new substance. For a campaign, this transformation is as much a psychological exercise as a narrowly political one.

An example of the politics-as-chemistry phenomenon came in 1992, when Bill Clinton was trailing badly after a primary season in which he became known largely for personal scandal and political calculation. But his selection of Al Gore as running mate transformed his prospects, projecting an appealing image of two young and serious-minded moderates, and giving voters occasion to look anew at Clinton's leadership traits. He vaulted into a first-place position that he never surrendered, not because voters were necessarily ecstatic about Gore - a presidential also-ran four years earlier - but because the choice told them something important about Clinton's values.